This chapter is relatively straightforward and may not need too many notes to go with it. So here they are! First is my outline from previous years:

- Qualitative vs quantitative research. Pros and cons of each. pp. 32-35

- Kinds of research/research activities pp. 38-44

- Literature review

- Competitive audit

- Interview: stakeholder, subject matter expert, customer, user

- User observation/ethnographic observation

- The Persona Hypothesis p. 46

- Interview Strategies/Best Practices p. 51-55

This outlines can be re-phrased to give us a set of important points to focus on for this chapter:

- Should we go after qualitative or quantitative insights from research?

- What kinds of research should be doing? In what order?

- What is meant by the “Persona Hypothesis”? How is it related to personas as design artifacts like we saw in I300?

- How should we carry out interviews?

Qualitative vs Quantitative

Quantitative essentially means we can measure a value (“how much”) and associate a number with something. We saw some quantitative research in I300, like when we measured the movement time and calculated an index of difficulty when looking at Fitts’ Law. Most interaction design research is not like this kind of fundamental, lab-based HCI research. Most is instead qualitative, pertaining instead to the quality of something (“how good”, etc.). If we seek to discover users goals and understand how and why they carry out the activities they do, then we are likely to be looking for qualitative information.

Alan Cooper also points out that in a business context when designers are doing UX work, there may be quite a bit of quantitative data from market segmentation, demographic data, and so on. This data is not useless, but the temptation to rely on it too much should be avoided because the real insights about user’s behavior will be qualitative instead.

Different Research Activities

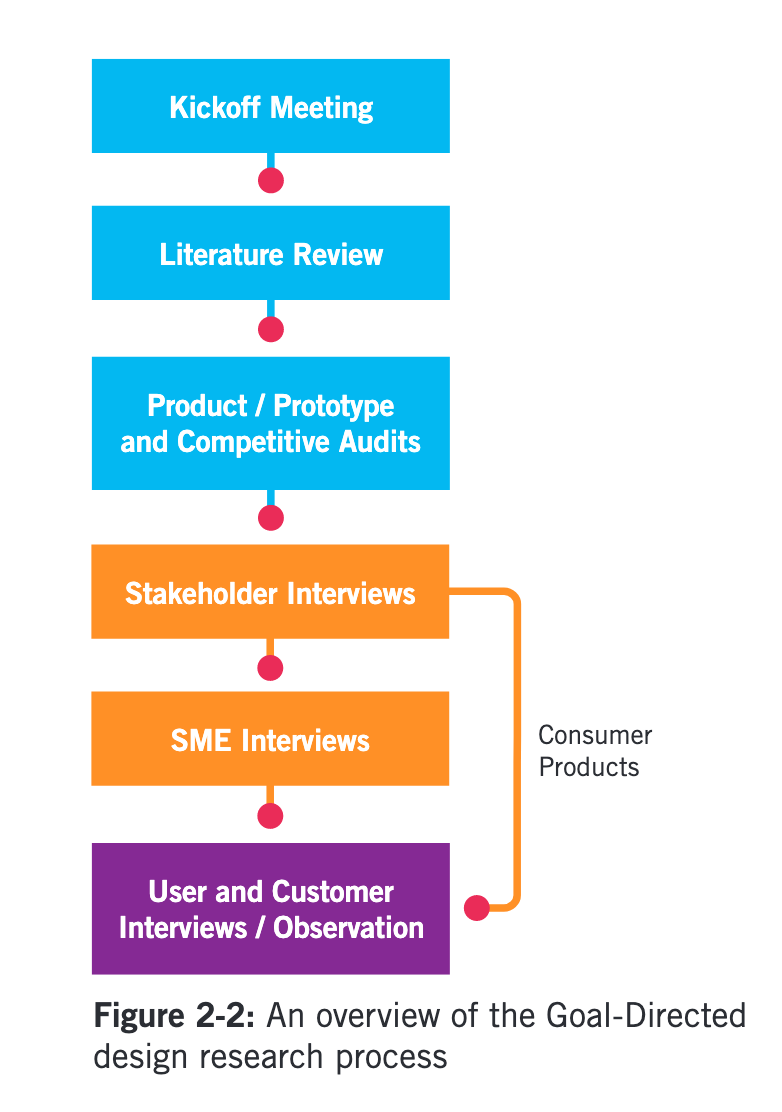

Figure 2.2 shown below is helpful because it lists a typical UX research process and indicates a useful order to carry out certain research tasks.

The research activities we can carry out are:

- Literature Review – See what others have written or researched and documented about the problem area or other relevant areas

- Competitive audit – What competitors are there? How have they solved the design problem, and how can what you’re designing be differentiated from them?

- Stakeholder Interviews

- Subject Matter Expert (SME) Interviews

- User Interviews or ethnographic observation

Note that Cooper recommends talking to users last; this is a “last but not least” situation. The designer needs to have some understanding or background in the problem domain in order to better help potential users when interacting with them. This is a big reason why seeking out subject matter experts happens first; they are experts in the problem domain and can describe it. Users may or may not be experts in the domain, and having a background in the domain can allow the design to critically evaluate what the users say and do.

With competitive audits, be very liberal about what is considered a competitor. Apps or products that don’t directly compete but solve a related design problem are very much worth analyzing because they will show you potential design solutions to your related problem. When carrying out a competitive audit of another product, don’t just list it’s features, and don’t just assess its look and feel. Look at the layout and the task flows. How is it set up to let users navigate efficiently through the app? What things do you see that could be done better, and what things can’t be improved upon? What conceptual model is the app striving to support? These are not fast or easy questions to answer; it takes time to look at a product and analyze its design in this fashion.

We can’t say too much about stakeholder interviews in I441 since we’re not designing in a business context. Instead we focus on user interviews and SME experts. One important task is to determine how relevant SME interviews are for a design project. Certain domains (e.g. designing an app for bioinformaticists or one for professional graphic designers will by necessity involve dealing with expert users. Design an app in a more everyday domain area may not.

When focusing on users, note it’s important to deal with the context in which users are carrying out tasks or accomplishing goals. What’s going on around them while they’re doing things relevant to the product being designed? Are they distracted by noises? Are they having to operate a machine with one hand leaving only one hand to operate the product? A good way to learn this information is to observe rather than interview. If interviewing, focus on context and attitudes. Don’t ask users which features they would like, and don’t ask them what kind of user interface they would like. Instead ask them how they think about their activities or ask them about frustrations with existing products they have to use for them.

The Persona Hypothesis

The persona hypothesis is a strange phrase, but it’s worth paying attention to. We saw in I300 that a persona is a fictitious description of a user. It’s purpose is to represent through a made-up individual an entire category or class of users. This concept is useful simply because it’s easier to design for one person (even an imaginary one) than for an abstract group of people.

A hypothesis is an idea that can be tested. In this case, the idea to be tested is a statement of what the categories of users are; i.e. who the personas are. The persona hypothesis is tested by carrying out research and follow-up analysis of that research to determine the categories of users.

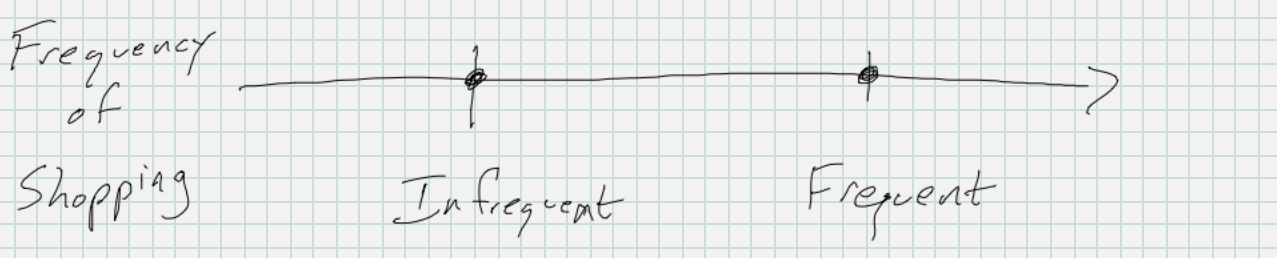

A lot of emphasis has been placed on categories of users here because one or more personas represent each category. Alan Cooper emphasizes the use of behavioral variables to identify these categories. A behavioral variable is often qualitative rather than quantitative, and it can be thought of like a number line with a few ticks marks on it. What the variable represents and what the value or tick marks are will depend on the research. Cooper gives an example about frequency of shopping with two values: frequent and infrequent. That would give us this number line:

If this is our only behavioral variable and we have these two values with research indicating enough potential users fall into each category, then we have two classes of users.

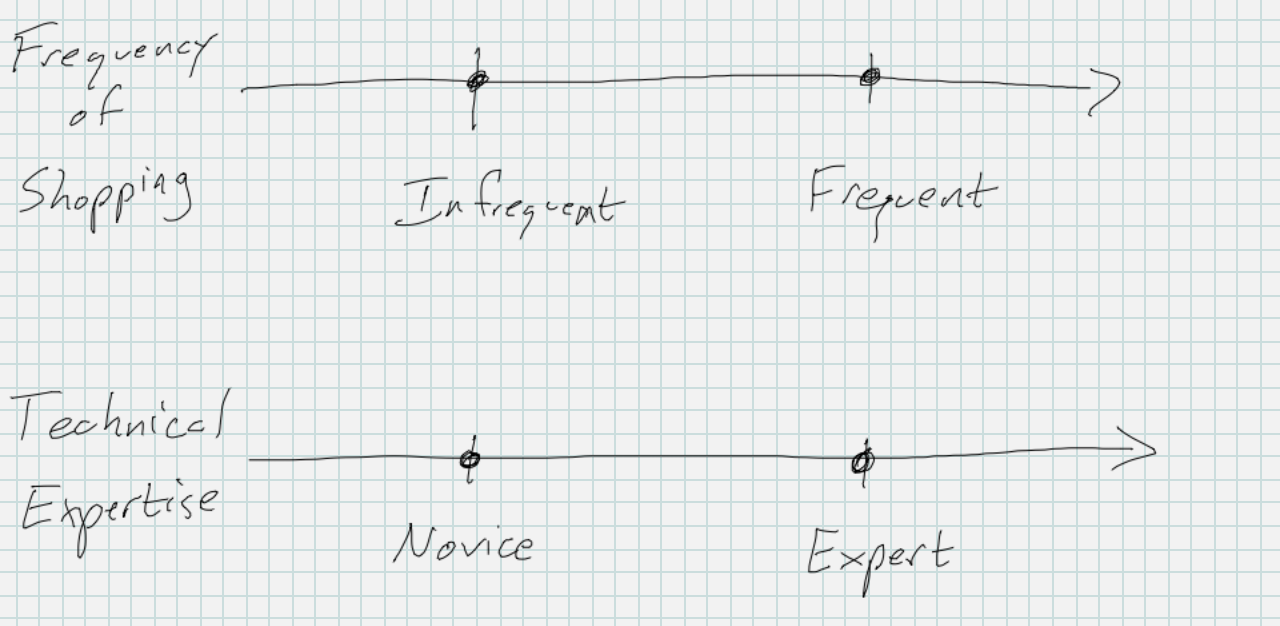

On the other hand, if we have a second variable “technical expertise” we may end up with something that looks like this.

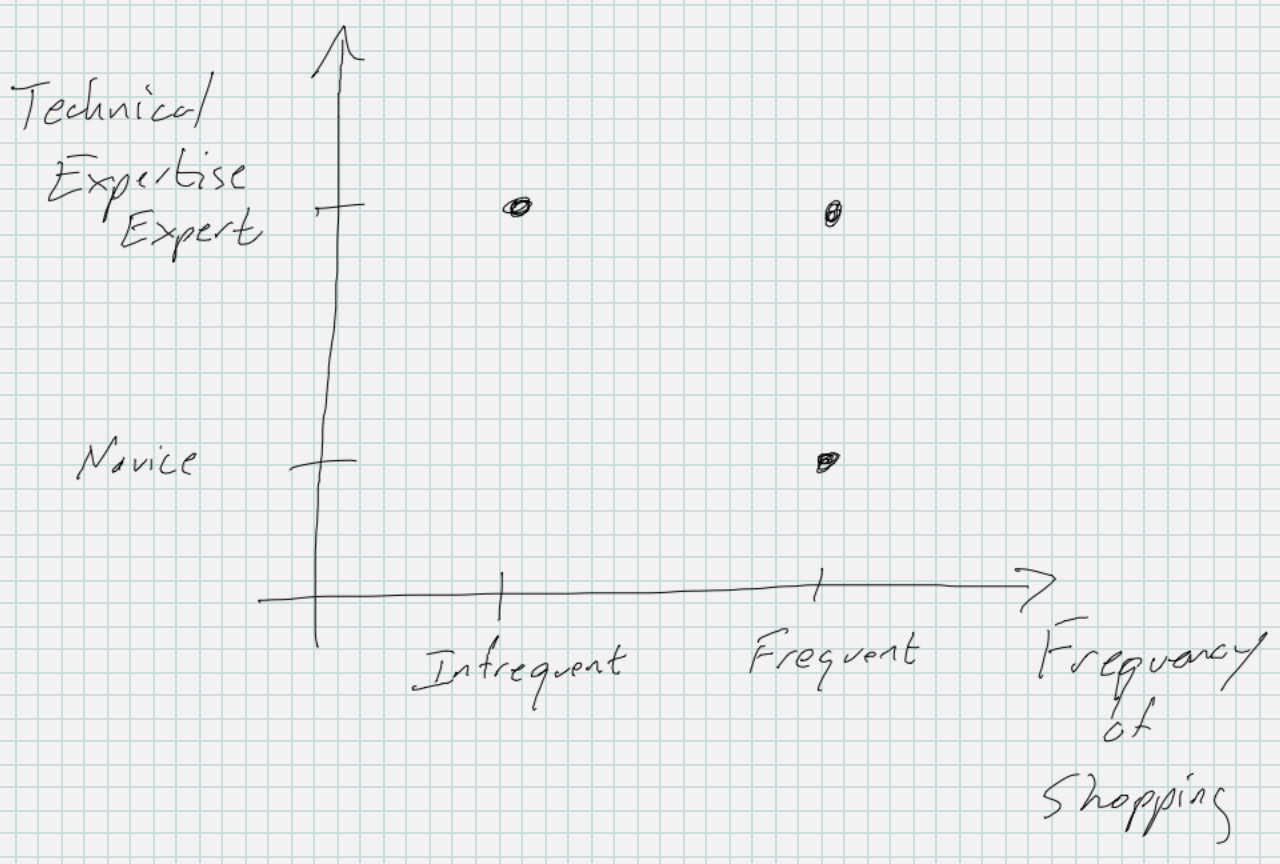

We might be tempted to assume we have 4 classes of users, but we need to be careful. Upon further analysis of our research, we may realize the users are distributed like

In this case, if we notice that infrequent shoppers never seem to be novice users, then we end up with 3 categories instead of the 4 we would have originally suspected. At this point, we can state the persona hypothesis that we have those 3 classes of users, and we will develop at least one persona for each class of user to give us a design target.