Chapter 2 was about carrying out research in order to reach the point where categories of users can be defined with the Persona Hypothesis. This chapter, Chapter 3: Modeling Users: Personas and Goals, is about how to formulate the Persona Hypothesis. From the last notes we saw how behavioral variables can help us identify the categories of users in a fairly precise way. We didn’t exactly see how to reach the point where those variables are identified and users’ values on those axes determined. This chapter can help us do that.

Here is the high-level description of the chapter:

- Personas represent user roles pp. 67-71

- Understanding & Describing Goals

- Determining Personas pp. 82-85

- Group by roles

- Identify behaviors

- Activities

- Attitudes

- Aptitudes

- Motivations

- Skills

- Map users to behaviors

- Primary vs secondary personas pp 88-89

Alan Cooper was the main early proponent of using personas in user interface design, so they receive a correspondingly heavy emphasis in his book. Not every interaction designer uses personas, and not every one that uses them uses them to the extent that Cooper emphasizes. In order for you to determine whether they are a tool you would use professionally or not, it’s useful to understand Cooper’s arguments and try them out in projects this semester.

With that background, Cooper begins the chapter touting the advantages of using personas. One big advantage is that they help avoid having what he calls “the elastic user”. An elastic user is one that stretches or changes to meet any design need that is thought of. Not having a firm idea of who your user is means that you’ll never be sure if decisions you make are right for your user or not. If you can’t be sure, you’re likely to end up with a one-size-fits-all solution that in reality fits no one very well. Personas, because they are well defined according to what we saw previously, help avoid this pitfall. Any design choice can be evaluated according to the question “Is this what [name of Persona] needs?”

After that Cooper re-emphasizes that personas represent a set of behaviors. We’ve described each one as representing a category of users. So we can equate a category of users with a specific group of behaviors. Emphasizing behaviors is important, because it connects to the behavioral variable idea. It’s also important because it de-emphasizes other distinctions that may not be important. The age of the persona does not matter except in terms of how it makes their behavior different. Likewise with other demographic data that traditionally provides market segmentation and other business data; it only matters for personas insofar as the groups acts differently.

Goals in more detail

Goals are the things that motivate users’ behaviors, so determining and then articulating goals is a necessary first step towards creating good, useful personas. Cooper defines three different kinds of user goals and relates them to the three levels of cognitive processing introduced in I300 from The Design of Everyday Things relevant to the Seven Stages of Action.

| Type of Goal | Design or Cognitive Level |

|---|---|

| Life Goal | Reflective |

| End Goal | Behavioral |

| Experience Goal | Visceral |

Visceral goals are the users immediate, “gut” reaction to an experience. In terms of goals then, they answer the question “How would I like to feel when I use this product?” It’s tempting to state that the users experience goal is “good” or “nice” or something else suitably vague. it’s better to have more precise goals like “organized”, “efficient”, “accomplished”, “powerful” that give you a more specific design target.

End goals are the intermediate ones, and end goals are the most important ones to get right with respect to goal-directed design. They are a description of what users want to achieve. Users achieve them right after (at the end) completing a task or activity and not so much while completing it (visceral is the while). Defining these are critical, for they are a descriptions of the things users need to do with a product. Some examples are given in the text:

- Get the best deal

- Find music that I’ll love

Note that they are super detailed. It’s about finding a deal without regard to something more feature-driven like “search for coupons from local stores” or “see what music my friends like”. The end goals need to be articulated first at the right, high level so that the more detailed ways to achieve these goals can then be worked out.

Life goals, as Cooper notes, are more long term and not always related to the product being designed. They can be important and helpful to define for personas, but they will not necessarily be in terms of the interface you’re designing.

Defining Personas

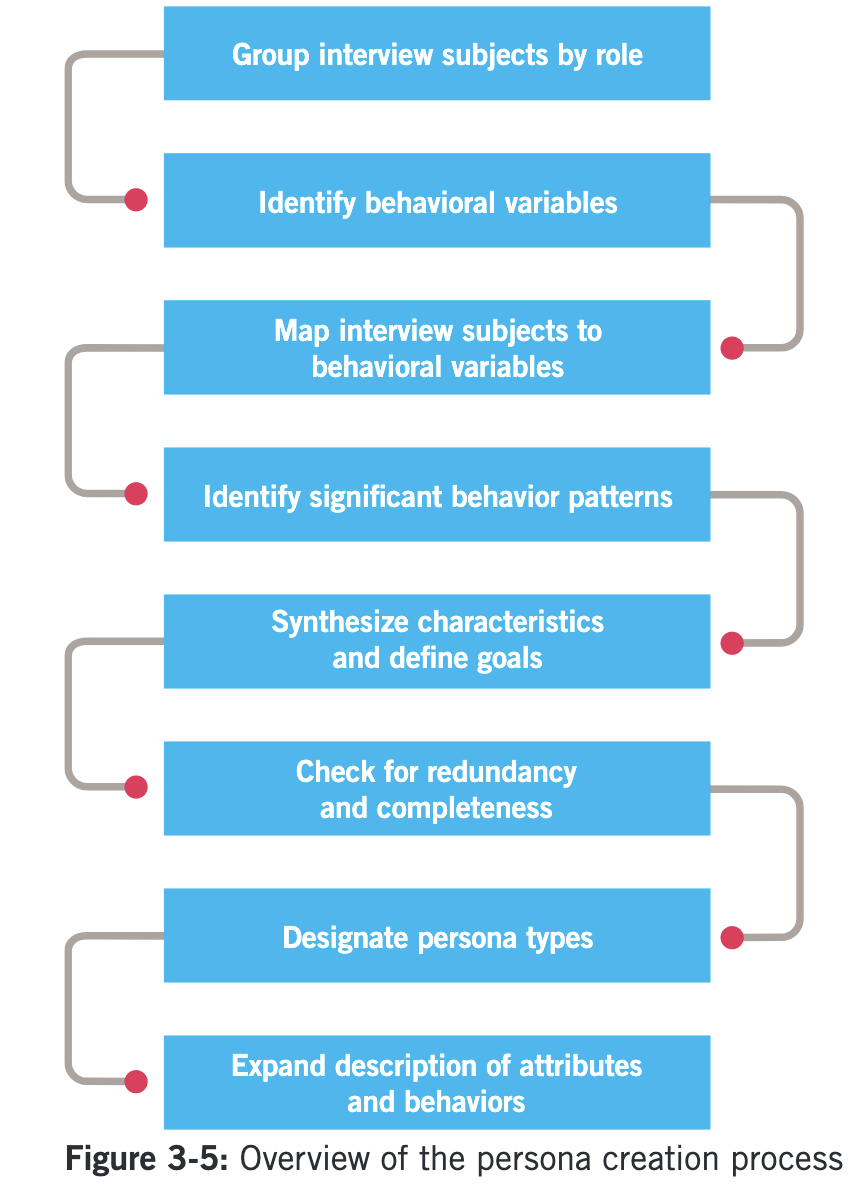

Cooper provides a process for constructing personas.

The process overall describes in more detail what we saw in the previous notes about using behavioral variables. The two parts of the process the benefit from further description are identifying the variables and identifying significant behavior patterns.

Identifying Behavior Variables

Cooper provides a handy list of ways to find these variables from interview data or user observation.

- Activities – What the user does

- Attitudes – What the user thinks

- Aptitudes

- Motivations

- Skills

Note that when we identify a variable, we also must identify values for that variable. For each category of users, we will have specific ways to describe their attitude, and then we can use them to build the persona.

Identifying Behavior Patterns

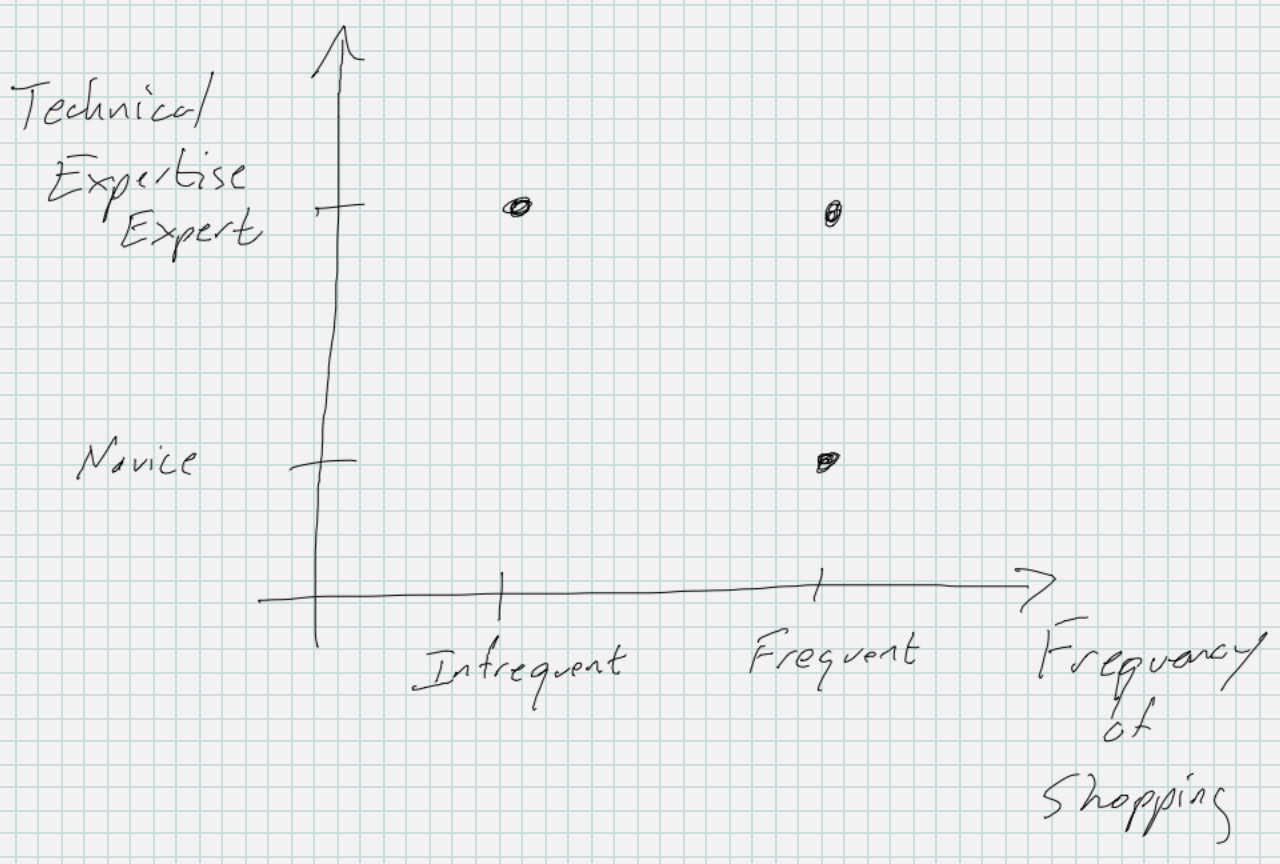

This sounds likes a big, new topic, but we actually covered it with the Persona Hypothesis. Once we recognize a cluster of values defines a group of users, we have done that. In this example we saw previously

This kind of view of behavioral variables led to three groups of users; each group has its own pattern of behaviors. This diagram is overly simplified because we only have two behavioral variables, and we can then sketch it out and visualize it. In a real project, we may have many more behavioral variables, and then the process becomes a little fuzzier. In reality we will be looking at values in common between users we interview or observed, and we will try to “eyeball” these groups.